Despite abundant innovation and social impact potential, circular economy ventures in Africa remain among the least funded climate solutions on the continent. It’s time for capital and policy to catch up.

Across the continent, plastic waste clogs rivers, suffocates marine life, and spills into communities from Lagos to Nairobi. But beneath this crisis lies a broader opportunity: a shift from linear consumption to circular economies that regenerate, reuse, and reimagine resources.

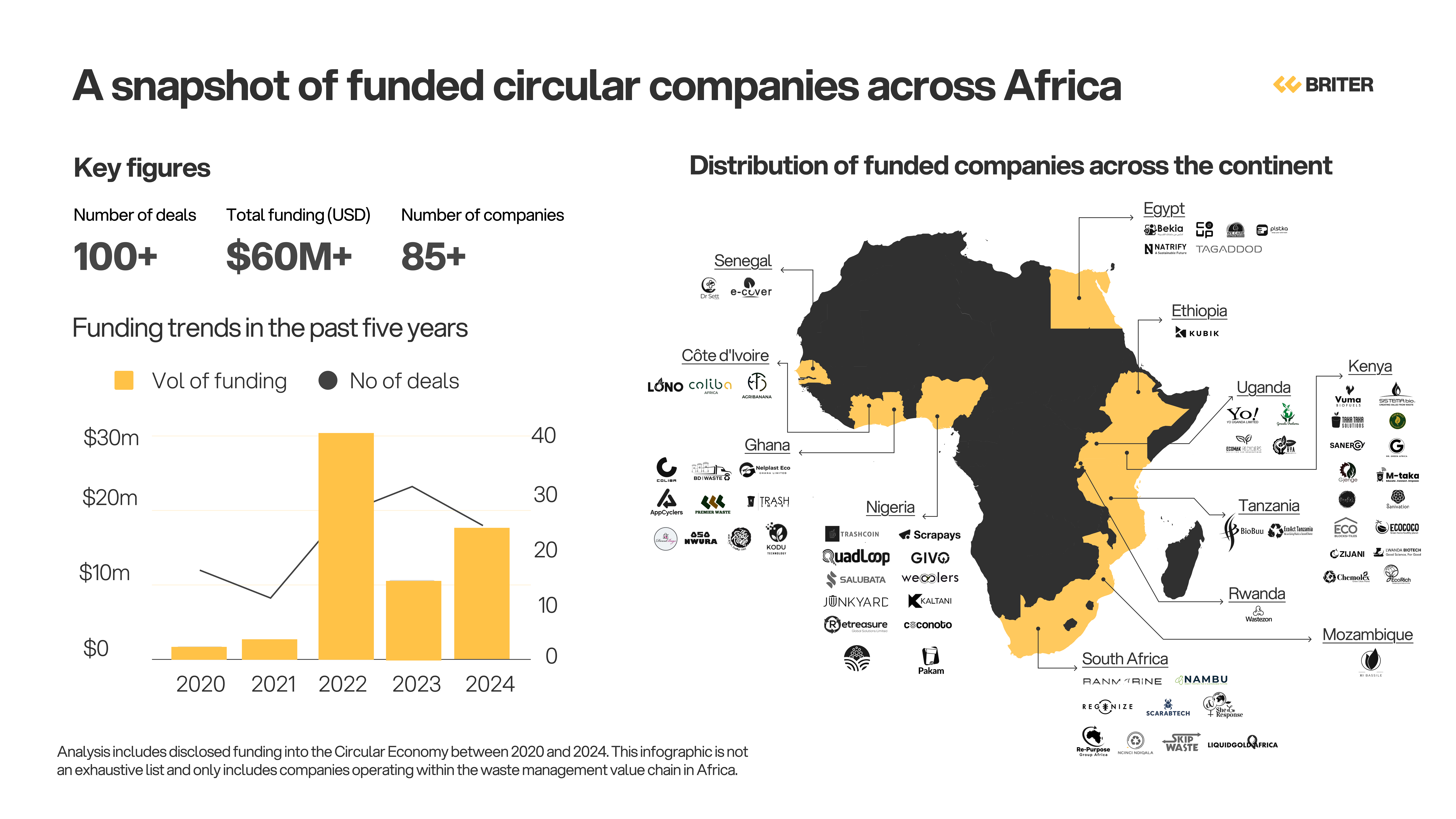

Circular economy models — spanning reuse, recycling, and repurposing — are emerging in African cities where state-led waste systems are broken or non-existent. Entrepreneurs are responding with asset-light business models, tech-enabled collection systems, and recycled material supply chains. Yet despite the sector’s growth potential, it remains chronically underfunded. According to data from Briter Intelligence , between 2015 and 2024, just 131 deals were recorded in the sector across the continent, raising a cumulative $89.6 million, with a median deal size of only $55,000.

“Circular economy innovation in Africa will thrive when we stop seeing waste as an afterthought,” says Dianah Irungu, Investment Associate at the Global Innovation Fund (GIF). “We must start building entire business models around resource regeneration.”

Entrepreneurs at the edge of infrastructure

In Addis Ababa, Kubik is turning waste into walls. Its modular building blocks — made from hard-to-recycle plastics — are faster to install and five times less carbon-intensive than cement. The company has built over 2,600 sqm of walls, recycled 232,000+ kg of plastic, and empowered over 600 female waste collectors.

“We treat plastic not as a problem but as an industrial input,” says Kidus Asfaw, Kubik’s CEO. “We’re not in the business of making bricks. We’re designing supply chains that rewire how African cities build and grow.”

In Cairo, Bekia uses a cashback-powered app to incentivise households and corporates to sort their waste. The platform collects 12 tonnes of PET plastic monthly, offering clean, segregated waste to recyclers while helping users track the impact of their emissions.

Founder Alaa Afifi describes Bekia as an “asset-light logistics layer” between individuals, waste collectors, and industrial recyclers. But scaling remains hard. “You can’t change the mindset of millions in five years,” he says. “We need regulation, corporate accountability, and aligned incentives.”

From Lagos to Nairobi, startups like Wecyclers , Mr. Green Africa , and Recuplast are proving that circularity is not just about recycling; it’s about redefining how consumption, labour, and infrastructure intersect.

Why circular solutions struggle to scale

Despite growing demand and proven use cases, circular economy ventures in Africa remain structurally underfunded. Compared to the hundreds of millions raised by energy startups each year, funding for circular models has been a fraction — spread thin across years, deals, and dozens of countries.

This funding gap stems from five intersecting barriers:

- Informal supply chains with little to no formal protections make scale and traceability difficult.

- Weak enforcement of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks limits incentives for companies to support recycling or reuse

- Recycled products are undervalued and struggle to compete with subsidised virgin materials

- Lack of anchor demand from large public or private buyers reduces market stability for circular solutions

- Mismatched capital structures mean few investors are willing to accommodate the long cash cycles and infrastructure-heavy nature of circular economy models

“This is not a failure of innovation,” says Irungu. “It’s a failure of financing architecture and policy alignment.”

What do investors look for in Africa’s Circular Economy?

At the Global Innovation Fund , Irungu and her team evaluate circular economy startups through five interlocking criteria.

1. Policy resilience over policy reliance: Governments across Africa have introduced bans on plastics, and EPR frameworks are gaining traction. But enforcement is inconsistent. For investors, startups must demonstrate not only that they benefit from regulation but that they can operate effectively without it. “We look for companies that can survive — even thrive — in policy vacuums,” says Irungu. “The best ones don’t wait for enforcement. They create operational resilience through design, data, and community-level trust.”

2. Supply chain maturity with informal integration: More than 60% of Africa’s recyclable waste is collected by informal workers. “The most promising companies have inclusive sourcing strategies,” Irungu notes. “They ensure consistency, quality control, and long-term price stability, while also sharing value with informal actors.”

3. Validate market demand beyond price: Most circular startups compete with virgin materials that are cheaper, heavily imported, or subsidised. Competing purely on price is a losing game. “We want to see startups competing on value, durability, and compliance,” says Irungu. “Whether through off-take agreements, ESG mandates, or product specs that meet green building standards.”

4. Access to blended capital: Circular ventures often fall into the “missing middle”. They are too operationally heavy for venture capital, too early for debt, too complex for grants. Irungu notes that startups that understand how to combine grants, concessional debt, and catalytic equity — even if they haven’t secured it yet — signal real readiness.

5. Governance that signals scalability: Finally, governance is not an afterthought. Investors look for discipline, clarity, and systems-level thinking, even before Series A. “Even if a company isn’t backed by a DFI yet,” Irungu concludes, “we want to see the discipline of transparent reporting, operational dashboards, risk management. It signals scalability.”

How can we unlock more investment in Africa’s circular economy?

So what will it take to fund Africa’s circular future? We still have more questions than answers, but four priorities can help steer the discussion:

1. Policy + Infrastructure: Governments must do more than pass bans; they must enforce them, incentivise circularity, and invest in infrastructure that supports material recovery and traceability. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks are promising, but enforcement remains patchy. “There’s a positive shift in the way lawmakers across Africa are now taking steps to address plastic pollution,” says Abisola Richard-Ogbomo, founder of Cleaning ‘n’ More in Nigeria. “But what’s missing is stability. These systems have to be grassroots-based, and the informal players (waste pickers and scavengers) must be brought into one flowing system.”

2. Blended Capital: Circular ventures are operationally heavy and infrastructure-dependent. They do not scale on venture capital alone. Grants, concessional debt, and patient equity are essential to build the basic systems — sorting hubs, logistics, traceability — on which circular models depend. Richard-Ogbomo suggests creating pooled funding tools that blend donor capital with institutional investment and grassroots grants.

3. Investors look for evidence of future demand: Offtake agreements, ESG procurement mandates, and circularity certifications can help de-risk the demand side for investors. “The market for green products is there,” says Irungu. “But you have to prove the value beyond just being ‘sustainable.”

4. Cross-sector collaboration: FMCGs and manufacturers must stop treating waste as a PR problem. They are central to solving it. Richard-Ogbomo notes that firms like Coca-Cola and Nestlé have begun supporting plastic recovery initiatives, but urges them to embed circularity into their core operations, not just their CSR programs.

Circular models won’t scale on goodwill and pilots. They need roads, rules, and risk-takers. Until then, Africa’s climate potential is being dumped at the curb. Funders face a fragmented ecosystem and limited tools to navigate it. Unlocking Africa’s circular economy—and its broader climate innovation potential—requires rethinking how capital is deployed. This means supporting ventures at different stages with flexible instruments such as blended finance, convertible grants, and milestone-based funding.

We explore these themes in our upcoming Climate Financing Playbook with SPARK, a project dedicated to strengthening African tech ecosystems to support climate-smart, gender-responsive, and research-based innovations, supported by GIZ. Pre-register for the full report or download key insights here .